INTRODUCTION

Cepaea hortensis (O. F. Müller, 1774) is a species of Central European origin, also native to large areas of Northern and Western Europe (Taylor 1914, Boettger 1926). Recently, introduced populations of C. hortensis have been increasingly recorded in Eastern Europe (Egorov 2015, 2018, Kruglova & Kolesnik 2017, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a, Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024, iNaturalist 2025), which could be facilitated by global climate change and the activities of numerous garden centres importing seedlings of garden and ornamental plants from abroad (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022a, Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024). A similar and even more pronounced trend is now observed for the related species Cepaea nemoralis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Gural-Sverlova et al. 2021). In Western Ukraine, there have also been some cases of joint introduction of two Cepaea species together with ornamental plants (Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024).

C. hortensis was first successfully introduced to Western Ukraine apparently in the second half of the 20th century (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a). Some earlier mentions of this species for the Khmelnytskyi region (Belke 1853, Novytskyi 1938, Put 1954) were most likely based on erroneous identifications of the native Caucasotachea vindobonensis (C. Pfeiffer, 1828), widespread in Ukraine. None of the authors mentioned above specialised in the study of land molluscs, so such errors might be expected. In particular, Belke (1853) does not mention C. vindobonensis, which is common in Kamianets-Podilskyi and its environs. By the end of the 1990s, C. hortensis became a typical representative of the urban fauna of Lviv (Sverlova 2002a). The dispersal of the descendants of the primary introduction of C. hortensis both in Lviv (Sverlova 2002a, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a) and in some other settlements of Western Ukraine (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a, 2023) was facilitated by planned landscaping with hedges made of ornamental shrubs.

In other parts of Ukraine, the first reliable records of C. hortensis were made only in the 21st century, mainly in recent years (Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024). This has been significantly aided by citizen science databases (iNaturalist 2025, UkrBIN 2025). The few earlier mentions for Central Ukraine published in the 20th century, in particular for Vinnytsia (Novytskyi 1938) and Kyiv (Put 1954), were apparently erroneous. Thus, different malacologists did not find C. hortensis in Kyiv either at the end of the 20th century (Tappert et al. 2001) or at the very beginning of the 21st century (Balashov 2008). The earliest reliable observation of C. hortensis in this city that we could find was in 2020 on Facebook. It is significant that the list of Novytskyi (1938) also contains other erroneous identifications, for example, Helicella itala (Linnaeus, 1758) or Chilostoma cingulatum (Studer, 1820), species not occurring in Ukraine.

In Lviv, the shell colour and banding polymorphism in C. hortensis has been periodically studied since the late 1990s (Sverlova 2001a, 2002a) and the early 2000s (Sverlova 2005) to now. This made it possible, firstly, to analyse the spatial (Sverlova 2001b, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022b) and temporal (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2018, 2022b) variability of the phenotypic composition using large quantitative material and compare it with populations of C. hortensis within the natural range (Sverlova 2002b, 2004). Secondly, we identified and described (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a, 2022a) a set of the colouration traits (phenotypic markers) that allows us to distinguish with high reliability the populations formed by the descendants of the primary introduction of C. hortensis to Western Ukraine from the results of later independent introductions or mixed populations. This will be described in more detail in Material and Methods.

Previously, the populations of C. hortensis formed by the descendants of the primary introduction of this species to Western Ukraine were known, in addition to Lviv, in some settlements of the Lviv region, at the biological and geographical station of the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv in the northwest of the Volyn region, in the cities of Ivano-Frankivsk (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a) and Ternopil (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2023). However, we assumed that they were distributed much more widely, especially within the administrative boundaries of the Lviv region, where C. hortensis is most common (Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024). Therefore, one of the main objectives of this study was to clarify the extent of distribution of the descendants of the primary introduction in the Lviv region and beyond. Considering the rather rapid spread of other colouration forms of C. hortensis from garden centres (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022a, Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024), this had to be done quickly, before the mixing of descendants of different introductions greatly distorted the original picture. For example, in Lviv, the colouration forms that are not typical for the primary introduction are still found very locally (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022b: fig. 3). Given the near-ubiquity of C. hortensis in this city, they remain, as it were, a “drop in the bucket”.

We also wanted to summarise all available and reliable data on the findings of various colouration forms of C. hortensis in Ukraine in order to create a basis for subsequent monitoring of not only the gradual dispersal of this species across Ukraine (Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024), but also the connection of this process with different “waves” of introduction.

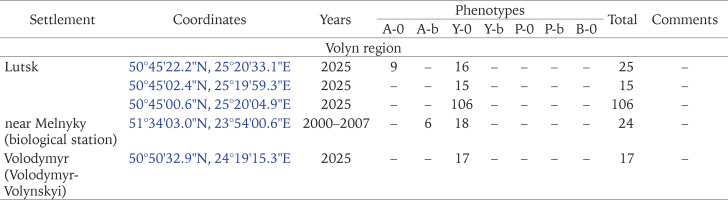

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We used the results of our own long-term research in Western Ukraine (from 1998 to 2025), some samples from other collectors, as well as additional sources of information: observations in citizen science databases (iNaturalist 2025, UkrBIN 2025), posts on the social network Facebook, and personal correspondence with the authors. These additional sources were taken into account only under the following conditions: 1) the location and time of observation were known; 2) observations were confirmed by photographs that allow the reliable identification of the species (C. hortensis) and the colouration of the shell (shell and body). The qualitative data for more than a hundred settlements from 18 administrative regions of Ukraine, obtained in this way, are summarised in Appendix 1.

Appendix 2 shows the quantitative composition of phenotypes in the samples we studied: a total of 139 samples and more than 10 thousand specimens from 55 settlements or their immediate surroundings and 5 administrative regions in the western part of Ukraine. For Lviv, only a few samples are given, containing regionally rare colouration variants. The phenotypic composition of numerous Lviv populations of C. hortensis formed by the descendants of the primary introduction was analysed in detail in previous publications (Sverlova 2001b, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2018, 2021a, 2022b, etc.). Appendix 2 does not include samples with less than 10 adults or their empty shells. The only exceptions are three smaller samples that showed signs of secondary introduction or a mixture of introductions.

Of the samples mentioned above, about two-thirds were collected only in 2023–2025 and are not referenced in any previous summary publications (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a, 2022a, 2022b, Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024). During this time period, we also first surveyed populations of C. hortensis in the Ternopil (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2023) and Rivne (Zdolbuniv) regions, in Lutsk (the administrative centre of the Volyn region), and in a number of settlements in the Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk regions. To date, the malacological collection of the State Museum of Natural History in Lviv contains conchological material from 62 settlements in Western Ukraine, marked with asterisks in Appendix 1.

Samples were usually collected at sites without significant anthropogenic barriers that would impede the movement of snails (Sverlova 2001b, 2002a, 2005). Their size most often did not exceed the diameter of the panmictic unit, which for Cepaea can be from 50–60 (Jones et al. 1977) to 100 m (Schnetter 1950). With a small number of snails, specimens collected from larger areas, even from different parts of the same settlement, could be combined into one sample. In Appendix 2, such samples are referred to as “composite”. All samples consisted of adult living individuals, and less often also their empty shells with well-preserved colouration. In addition, we noted the shell and body colouration in all adults and juveniles of C. hortensis found in the settlements we visited.

In settlements and their immediate environs, we paid particular attention to those types of landscaping that played and continue to play a decisive role in the initial colonisation of areas by C. hortensis. For the primary introduction of C. hortensis to Western Ukraine, these were old hedges made of ornamental shrubs (Fig. 1), less often also of maples, hornbeams, etc. In the second half of the 20th century, such hedges were often planted along streets, near railway stations, schools, hospitals, administrative buildings, as well as in parks and squares (Sverlova 2002a, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a). Having arrived there together with the plants, the snails then populated other suitable habitats due to their own locomotor activity, or by accidental or intentional transfers by people, especially children (Sverlova 2002a).

Populations of C. hortensis with signs of secondary introduction (mixture of introductions) were most often found near garden centres that import part of the seedlings sold from other European countries (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022a, Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024), as well as at sites with relatively young ornamental plantings (Figs 2–4), especially with the currently popular thujas, junipers, and other conifers. Junipers and other low-growing conifers from garden centres populated by Cepaea also provide reliable cover, helping to establish populations in new areas. For example, we observed many adults and juveniles of C. hortensis for at least three years even in such a limited space as shown in Fig. 5.

The shell ground colour was classified as white (A), yellow (Y), pink (P), or brown (B). As with the related species C. nemoralis (Gural-Sverlova et al. 2020: fig. 2B), we classified both all shades of pink (from pale and grayish pink to intense pink) and orange colour as pink. Usually, when studying the phenotypic composition in populations of both Cepaea species, white shells are combined into one group with yellow ones. At the beginning of our research, we used the same approach, considering all Western Ukrainian populations of C. hortensis known to us at that time to be monomorphic in yellow ground colour (Sverlova 2001a, 2002b, etc.). However, white shells, both banded and unbanded, are often found in different parts of the present range of C. hortensis (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022a: figs 6–7, iNaturalist 2025) and in most cases are easily distinguished from yellow ones. Long-term observations of Western Ukrainian populations of C. hortensis allowed us to conclude that the white ground colour in this species is the same heritable trait as yellow (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022a). Furthermore, the clear separation of white and yellow banded shells is crucial for studying the history of C. hortensis introductions to Ukraine (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a, 2022a).

Outside of Ukraine, the white ground shell colour in C. hortensis is found in places in many European countries, particularly in England and in southern part of Central Europe: the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Austria (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022a: fig. 7), as well as in North America. This was demonstrated by our analysis of thousands of photographs in the citizen science database iNaturalist. In introduced Eastern European populations outside Ukraine (Belarus, European part of Russia), this variant of ground colour is also present, although not always (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a). In particular, the malacological collection of the State Museum of Natural History in Lviv contains white banded and white unbanded shells of C. hortensis from the town of Vidnoe, Moscow region.

To determine the ground colour in banded shells, we examined primarily the shell apex and the area near the umbilicus (under the bottom band). At these fragments, the ground colour is usually much more pronounced, especially at the apex. In questionable cases (light yellow or pale pink shells, damaged periostracum, collected empty shells as well as shells that had been stored in a museum collection for a long time), these fragments were moistened with water, which made the colour more visible. In unbanded shells, their entire surface could be wetted.

Shells that did not have even a slight yellowish tint over the entire surface in unbanded shells, or at the apex and near the umbilicus (see above) in banded shells were considered white. In living snails, especially juveniles, white shells often appear snow-white (Fig. 6). Periostracum that has darkened due to external influences or after storage in a museum collection may somewhat distort the original colour. But even then, white shells do not acquire a distinct yellowish tint, and they can be reliably distinguished from yellow ones. In addition, the periostracum darkens uniformly over the entire surface of the shell. Therefore, the ground colour of white banded shells also remains uniform, unlike yellow banded ones, see above.

Figs 1–5

Examples of urban landscaping that promotes the spread of C. hortensis (2 – Ternopil, 4 – Zalishchyky, Ternopil region, the rest in Lviv): 1 – a fragment of an old hedge from ornamental shrubs, populated by descendants of the primary introduction; 2–4 – younger plantings where secondary introductions were recorded; 5 – an example of temporary survival in a limited area

Figs 6–11

Descendants of the primary introduction (6, 8) and later independent introductions (the rest) of C. hortensis to Ukraine: 6, 9 – Lviv; 7, 10 – Ternopil; 8 – Dubliany, Lviv region; 11 – Solonka, Lviv region. For more details, see Material and Methods

The descendants of the primary introduction have no more than three variations of the shell colouration (yellow unbanded, white unbanded, white banded), and only a light body, without pronounced grayish or reddish (brownish) pigmentation (Fig. 6). Such populations can be reliably diagnosed by the complete absence of banded shells with a non-white ground colour in combination with a light body colouration in all individuals (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a, 2022a). In contrast, yellow banded shells are common throughout the present range of C. hortensis (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022a, iNaturalist 2025). They are frequently found in both natural and other introduced populations (Egorov 2015: fig. 3, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a, iNaturalist 2025), including secondary introductions of this species to Western Ukraine (Fig. 7). This is also true for the clearly expressed variability in the body colouration (Fig. 7). In addition to yellow banded, descendants of secondary introductions may have pink (Fig. 7, 9) and occasionally brown (Fig. 9) shells.

Hereinafter, we designate as “dark body” (DB) any variations of its colouration that are not found in the descendants of the primary introduction. It may be a dark grey (almost black) body with the same dark sole. Another common variant is a light sole but a distinctly greyish back, often with a clearly visible narrow light stripe down the middle (Fig. 7, right).

Descendants of the primary introduction have the light shell lip typical of C. hortensis. Only occasionally can one see single specimens with a slight pinkness on the parietal wall of the aperture and/or on the lip part near the columella (Fig. 8). Following Schilder & Schilder (1957: 163), we did not consider this to be a manifestation of the dark lip, a heritable trait locally found in natural (Schilder & Schilder 1957: map 66, Ożgo 2010) as well as introduced Eastern European populations of C. hortensis (Egorov 2018, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a, 2022a). In Western Ukraine, the true dark lip in C. hortensis was first recorded only in 2019. It is pigmented along its entire length (from pink to reddish brown colour, sometimes it can appear almost black) and is usually present in all pink shells in the population, less often also in brown ones (Fig. 9) or in some yellow individuals.

As a result of secondary introductions, the phenotype 10305, a banded shell with the absence of the second and fourth bands (Fig. 10) has recently appeared in Western Ukraine (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2023). This is another colouration trait that is locally distributed in the natural range of C. hortensis (Schilder & Schilder 1957, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2023). Schilder & Schilder (1953, 1957) even included it among the “consubspecies” of C. hortensis they proposed, together with unbanded, mid-banded, and five-banded shells with discrete or fused bands.

The appearance of shells with clear hyalozonate (completely colourless and transparent) bands (Fig. 11) in several populations of C. hortensis in Western Ukraine is also probably associated with secondary introduction(s). Previously, in populations formed by descendants of the primary introduction, we sometimes found single shells with unclear bands, or more often, traces (fragments) of them. They were in places very weakly pigmented, in places colourless and transparent (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a: fig. 6C). Since these usually appeared on yellow shells (and the descendants of the primary introduction completely lack yellow banded shells, see above), we considered them as modifications (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a). In contrast, at some sites with signs of secondary introductions (yellow banded shell, dark body), hyalozonate bands were not only very clear and completely colourless, but could also be present in 20–25% of banded individuals.

Depending on the phenotypic composition of C. hortensis, the analysed settlements (Appendix 1) were divided into 5 groups:

PrI – so far only populations formed by descendants of the primary introduction have been discovered;

Mix – there is reliable evidence of both primary and one or more secondary introductions (usually there are local “inclusions” of other colouration traits against the background of widely distributed descendants of the primary introduction);

SeI – there are colouration forms that are absent in the descendants of the primary introduction; there is no clear evidence of primary introduction (absent, insufficient data);

Ind (indeterminate) – single phenotypes were recorded, which may belong to both primary and secondary introduction (most often a yellow unbanded shell and a light body);

BB – a specific composition of phenotypes registered in the adjacent areas of Ternopil (Berezhany and its immediate surroundings) and Ivano-Frankivsk (Burshtyn) regions, for more details see Results and Discussion.

Designations of the main colouration traits mentioned in the article (in alphabetical order):

– A-0 – white unbanded shell;

– A-b – white banded shell;

– B-0 – brown unbanded shell (brown banded shells have not been found in Ukraine);

– DB (dark body) – any colouration that is noticeably different from the light body in the descendants of the primary introduction, see above;

– DL – dark lip, from pink to reddish-brown along the entire length;

– P-0 – pink unbanded shell;

– P-b – pink banded shell;

– Y-0 – yellow unbanded shell;

– Y-b – yellow banded shell.

RESULTS

Populations formed by descendants of the primary introduction of C. hortensis to Western Ukraine are distributed throughout the Lviv region (Fig. 12). They are also common in Ivano-Frankivsk and have been recorded in some other settlements of the Ivano-Frankivsk region (Bolekhiv, Herynia, Rohatyn). With a high probability, these include also all finds in the Lviv region, all or most finds in the Ivano-Frankivsk region, marked on the map as “indeterminate” (Fig. 12) due to limited data.

Fig. 12

Analysed records of C. hortensis in Ukraine (top) and its Lviv region (bottom), designated according to the colouration variants found. For legend, see Material and Methods. The map is based on the data summarised in Appendix 1

Outside these two administrative regions, such populations were found in Ternopil (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2023) and the Volyn region (Lutsk and the biological and geographical station of the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv). In the latter case, C. hortensis could have been accidentally brought from the university botanical garden in Lviv together with seedlings of ornamental shrubs for landscaping the educational station. In Lutsk, no specimens of C. hortensis with a banded shell have yet been found (founder effect?). However, several hundred juveniles and adults from there, examined by us in 2025, had only light-coloured body. Furthermore, in some places we could see a connection between areas of the city colonised by C. hortensis and old hedges of ornamental shrubs. It is possible that the descendants of the primary introduction also inhabit Zdolbuniv (Rivne region), where light-bodied specimens of C. hortensis with yellow unbanded (usually) and white banded (a single case) shells have been recorded (iNaturalist 2025). However, this needs to be confirmed using more material. It is quite possible that they are also present in other administrative regions in the west of the country, for example, in the Transcarpathian region, where many localities are so far designated as “indeterminate” due to few observations (Fig. 12).

The combination of widespread descendants of the primary introduction with locally occurring signs of secondary introduction(s) has already been recorded in 15 settlements of the Lviv region (Appendix 1), most often in Lviv itself and its immediate surroundings (Fig. 12). Under such conditions, later invaders usually enter areas already colonised by C. hortensis, forming mixed populations. However, there are exceptions, even in Lviv, where descendants of the primary introduction are present almost everywhere. Usually these are small, recently landscaped sites near new buildings (Fig. 3). One such case was described in our previous publication, dedicated to the first record of another introduced snail, Harmozica ravergiensis (Férussac, 1835) in the Lviv region (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2024). There, the descendants of the secondary and primary introductions, collected at neighbouring sites, clearly differed not only in the shell and body colouration, but also in size (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2024: fig. 10). According to our observations in Lviv and the Lviv region, small sizes are generally characteristic of unmixed young populations of C. hortensis, which contain shells with a dark lip. If such populations are combined with the descendants of the primary introduction, then the sizes of even not typically coloured individuals (usually pink with a dark lip) gradually increase somewhat. Outside the Lviv region, the presence of descendants of C. hortensis introductions from different time periods in one settlement has so far been recorded only in Ternopil (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2023) and Bolekhiv, Ivano-Frankivsk region (Appendix 1, 2).

In two of the 15 settlements of the Lviv region mentioned above (Horodok, Pidbirtsi), the shell and body colouration variants of C. hortensis, absent in the descendants of the primary introduction, have so far been found only near garden centres. Overall, of the 17 garden centres in the Lviv region that we inspected from 2019 to 2025, signs of secondary introductions of C. hortensis were identified in 7 cases: Birky, Horodok, Pidbirtsi, near Davydiv and Sokilnyky, as well as near two recently closed garden centres in Lviv (Appendix 2). This almost always included variability in body coloration and the presence of yellow banded and pink shells. A dark lip was recorded in four cases, and brown ground colour in two cases. Some of the collected specimens were shown in previous publications (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a: fig. 3D, 2022: figs 4–5, 2023: fig. 2C, D). In the remaining cases, C. hortensis was not recorded (less often) or was represented by phenotypes common for Western Ukraine (more often).

In Lviv, studied since the late 1990s, we have found evidence of secondary introductions of C. hortensis only for 16 sites. The first record was made in 2019. Some of the collected specimens have been shown in previous publications (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a: figs 3B–D, 5C–D, 2022a: figs 2–3). At 14 sites, we collected samples presented in Appendix 2. In two more cases, we found single specimens with a shell colouration untypical for Western Ukraine (pink with a dark lip or yellow banded). In total, about two hundred sites were examined in Lviv, most of which were populated only by descendants of the primary introduction (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022b: table 2, fig. 3).

In Berezhany (Figs 13–14) and its immediate environs (the villages of Posukhiv and Rai, including the dendrological park of Rai) in the Ternopil region, we found populations of C. hortensis that were quite similar to the primary introduction. Their phenotypic composition can be briefly described as follows:

all banded shells have only one ground colour, but not white, as in the descendants of the primary introduction (Fig. 6), but light yellow (Figs 15–19);

all individuals have a light body (Figs 15–17, 19);

there are only three main variants of the shell colouration (Fig. 19).

The yellow pigmentation in banded shells can be so weak that it is barely noticeable at the apex and near the umbilicus, especially closer to the aperture. Depending on the lighting and angle, these shells can sometimes seem completely white, especially in photographs.

Similar samples were collected at three sites in the centre of Burshtyn, Ivano-Frankivsk region. Territorially, both localities (Burshtyn and Berezhany with adjacent villages) are not very far from each other, shown in black in Fig. 12. In Berezhany, quantitative collections (Appendix 2) were also made in the central part of the settlement, mainly at sites with low-trimmed boxwood hedges (Figs 13–14). During a qualitative examination, specimens of C. hortensis with such colouration were also found in other areas of Berezhany, including sites without young ornamental plantings, typical of secondary introductions. In general, in Berezhany and its environs, C. hortensis with this colouration was found in parks and squares, along streets, on household plots, and in the cemetery in the village of Posukhiv.

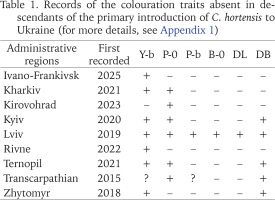

In contrast to Western Ukraine, there is still little data not only on the phenotypic composition of C. hortensis (Appendix 1), but even on the records of this species in other parts of the country (Fig. 12). Most of the data are taken from amateur observations posted in citizen science databases (iNaturalist 2025, UkrBIN 2025). In some cases (Zaporizhzhia, Odesa, Cherkasy, Simferopil) there are only photographs of a few specimens with a yellow unbanded shell, a colouration trait common for C. hortensis and present in most Western Ukrainian populations, regardless of their origin (Appendix 2). Some colouration variants indicating secondary introductions have been recorded in four regions: Zhytomyr, Kyiv, Kirovohrad, and Kharkiv (Fig. 12). These include a yellow banded and/or pink unbanded shell, and sometimes also a dark body (Table 1).

Figs 13–19

C. hortensis from Berezhany, Ternopil region: 13, 14 – collection sites; 15–17 – banded snails of different ages in habitats; 18 – adult banded specimens in the laboratory; 19 – three variants of the shell colouration

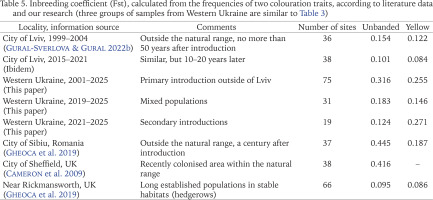

Table 1

Records of the colouration traits absent in descendants of the primary introduction of C. hortensis to Ukraine (for more details, see Appendix 1)

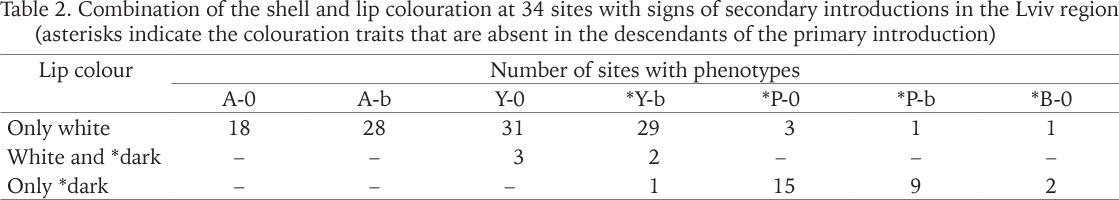

Table 2

Combination of the shell and lip colouration at 34 sites with signs of secondary introductions in the Lviv region (asterisks indicate the colouration traits that are absent in the descendants of the primary introduction)

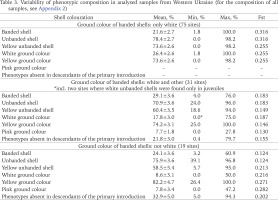

Table 3

Variability of phenotypic composition in analysed samples from Western Ukraine (for the composition of all samples, see Appendix 2)

In total, the colouration traits absent in the descendants of the primary introduction have already been registered in 9 administrative regions of Ukraine (Table 1). The greatest phenotypic diversity of C. hortensis is currently known for the Lviv region. Brown shells and shells with a dark lip were found only here. However, pink shells with a white lip are still rarely seen in the Lviv region (Table 2). This combination of the colouration traits is common for C. hortensis in general and has already been recorded in 5 other administrative regions of Ukraine: Kharkiv, Kirovohrad, Kyiv, Ternopil, and Transcarpathian (Table 1). At most sites of Lviv and the Lviv region where we found pink shells of C. hortensis, all of them were dark-lipped (Table 2). The phenotype 10305 has so far only been recorded in Ternopil and near the garden centre in Horodok. In both cases, such shells had a yellow ground colour and a white (Ternopil) or dark (Horodok) lip (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2023: fig. 2). Shells with true hyalozonate bands (see Material and Methods) in combination with a yellow or white ground colour were found at several sites in Lviv and the Lviv region (Hlyniany, Pidbirtsi, Solonka, Zymna Voda). At one site in Solonka, all banded shells had a yellow ground colour, and about 19% of them had hyalozonate bands. At one site in Hlyniany, half of the collected white banded specimens had hyalozonate bands, while all yellow banded shells had normally pigmented bands.

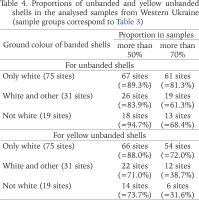

The variability of the phenotypic composition was analysed in three groups of samples differing in the ground colour of banded shells: only white, white and other, only non-white (Table 3). All samples were collected in Western Ukraine, where the listed groups most often correspond to primary introduction, a mix of introductions, and secondary introductions. The frequency of banded shells varied significantly in all groups, but its average value was always low: from 22% for the primary introduction to 29% for mixed populations. The prevailing phenotype was usually a yellow unbanded shell, which was particularly pronounced in the descedans of the primary introduction (Table 4). On average, every fifth specimen in the second group and every third specimen in the third group had a shell colouration that was absent in the descendants of the primary introduction (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Thanks to a fortunate coincidence, a unique situation has arisen in Western Ukraine that makes it possible to monitor the interaction of different introductions of C. hortensis – primary (no later than the second half of the 20th century) and secondary (no earlier than the end of the 20th or beginning of the 21st century). Our research in the Lviv region showed that the latter are associated with the activities of garden centres (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022a, Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024), many of which were founded no earlier than the beginning of the 21st century. Following the end of the deep economic crisis of the 1990s that accompanied the collapse of the former Soviet Union, the population’s standard of living began to gradually improve. The demand for ornamental plants has increased and they have begun to be actively imported from other European countries, primarily from Poland. Together with plants, snails of the genus Cepaea have begun to penetrate into garden centres and surrounding areas.

A similar situation has apparently taken place not only in other parts of Ukraine, but also in European Russia and in Belarus. This has led to an almost explosive increase in the number of new records of Cepaea and especially C. nemoralis in Eastern Europe in recent times (Egorov 2018, Balashov & Markova 2021, Gural-Sverlova & Egorov 2021, Gural-Sverlova et al. 2021, Gural-Sverlova & Kruglova 2022, iNaturalist 2025). C. hortensis is also increasingly spreading in Eastern Europe (iNaturalist 2025). However, this process is slower, and the number of known and especially described introduced populations of this species is noticeably smaller here (Egorov 2015, 2018, Kruglova & Kolesnik 2017, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a). The only exception is Western Ukraine (especially Lviv, see Introduction), where descendants of an earlier (primary) introduction of C. hortensis are widespread. As a consequence, C. hortensis is now a more distributed species than C. nemoralis only in Western Ukraine (Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024).

Table 4

Proportions of unbanded and yellow unbanded shells in the analysed samples from Western Ukraine (sample groups correspond to Table 3)

Populations formed by the descendants of the primary introduction of C. hortensis to Western Ukraine are recognizable not only by of the limited phenotypic diversity, as such a limitation can be observed also within the natural range of Cepaea, for example, in isolated island habitats (Schilder & Schilder 1953, Sverlova 2004). It is even more expected for introduced populations, which were often founded by a limited number of individuals with a limited genetic and phenotypic composition. Much more indicative for the primary introduction of C. hortensis to Western Ukraine is the absence of some features that are common for this species as a whole (yellow banded shell, distinctly greyish pigmentation of the body), while white banded shells are preserved in most populations. Such a specific phenotypic composition could have formed as a result of random population genetic processes: the founder effect or genetic drift at the initial stages of introduction.

Secondary introductions not only compensate for the strong phenotypic limitation of the primary one. Thanks to them, rarer colouration traits appeared in Western Ukraine, for example, pink (Cameron 2013: table 3) and especially brown (Cameron 2013: table 4) ground colour. This also applies to traits that are locally found even in the natural range of C. hortensis: dark lip (Schilder & Schilder 1957: map 66, Ożgo 2010), phenotype 10305 (Schilder & Schilder 1957: map 62, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2023). Of particular interest is the rather rapid dispersal of dark-lipped snails in Lviv and the Lviv region, which occurs through at least four garden centres: in Pidbirtsi (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022a), Horodok (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2023), Birky and between Sokilnyky and Lviv (data from 2024, see Appendix 2). Garden centres in the Lviv region compete rather than cooperate with each other. We can assume that different garden centres may have common sources of supply abroad, for example in neighbouring Poland, where the mentioned trait is locally found (Ożgo 2010).

The colouration traits absent in the descendants of the primary introduction are usually found in Western Ukraine at limited sites, rarely exceeding the size of a panmictic unit. Often, their clear connection with young ornamental plantings, especially conifers, can be traced. This does not depend on the geographical location of habitats, the phenotypic composition of populations, the presence or absence of descendants of the primary introduction in adjacent areas. All this supports the assumption that secondary introductions of C. hortensis began to occur recently. Despite this, even in a relatively small area (Lviv and its immediate environs) one can now see the descendants of different secondary introductions, clearly independent of each other and occurring through different garden centres. It is no coincidence that in some populations all pink shells have a dark lip, while in others they have a light lip. The same applies to the rarer brown shells (Table 2). In garden centres with different foreign suppliers, a mixing of several secondary introductions of different origins may also occur (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022a).

In Berezhany and its immediate surroundings in the Ternopil region, we discovered a set of C. hortensis phenotypes that differed from the primary introduction, but was distributed over a significantly larger area and in a wider range of habitats than is typical for the descendants of most secondary introductions. It is possible that C. hortensis entered the studied area before the active dispersal of this species through garden centres, see above. Unfortunately, it is impossible to establish even an approximate time of this penetration. There is not a single publication about the land molluscs of this area. Even in the malacological collection of the State Museum of Natural History in Lviv, which contains numerous samples from Western Ukraine from the second half of the 19th century to the present day, until 2024 Berezhany was represented only by some Unionidae shells (Bąkowski 1891, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2012). In the future, it would be desirable to conduct a more detailed study in both different settlements near Berezhany and the adjacent areas of the Ivano-Frankivsk region, where similar populations of C. hortensis have already been recorded (Burshtyn).

Our research confirmed that the descendants of the primary introduction are common throughout the Lviv region, and also expanded our understanding of their current distribution in other administrative regions of Western Ukraine. However, the exact boundaries of the territory they inhabited still require further clarification. In addition to the Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, and Volyn regions, populations formed by descendents of the primary introduction can probably be found also in the Rivne, Transcarpathian and Khmelnytskyi regions. However, it is already possible to say with confidence that even in Western Ukraine there are many settlements that are not yet inhabited by C. hortensis or that have only just begun to be colonised by this species due to secondary introductions. The latter may provide valuable information in the future for comparison with areas where secondary introductions are mixed with widespread descendants of the primary introduction (primarily the Lviv region).

In other parts of Ukraine, the probability of finding descendants of the primary introduction is low, but even here it, perhaps, cannot be equated to zero. For example, there are garden centres that operate online and send seedlings by mail throughout Ukraine. Terrarium keepers can also help to disperse such beautiful and rather large snails as Cepaea. Until recently, they could obtain C. hortensis for breeding only from abroad (more difficult) or from Western Ukraine. So far, it can be confidently stated that the colonisation of Central, Eastern and especially Southern Ukraine by C. hortensis began relatively recently (Gural-Sverlova et al. 2024), and secondary introductions play a decisive, if not the only role in this process. It is not accident that a number of observations of C. hortensis with a colouration different from the primary introduction are already known from Central and Eastern Ukraine. In the future, studies of the phenotypic variability of this species in Kyiv and its immediate surroundings, Zhytomyr, Kropyvnytskyi, and Kharkiv (Fig. 12) may be of particular interest.

From the very beginning of our research of the phenotypic composition of C. hortensis in Lviv (Sverlova 2001a, 2001b, 2002a, 2002b), and then in other settlements of Western Ukraine (see review in Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a: table 1), we noted a very high proportion of unbanded shells in most of the studied populations. In Lviv at the end of the 1990s, it amounted to, on average, about 80% (Sverlova 2001a, 2001b, 2002b, Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022b). This is despite the fact that many of studied sites were fragments of hedges, often additionally shaded by trees and/or multi-storey buildings. In one of the Lviv parks, studied in detail in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the average frequency of unbanded shells almost reached 70% even in shaded forest-like areas, increasing to 85% both at open sites with tall herbaceous plants and among ornamental shrubs (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a: table 2). The proportion of banded shells in the city remains low so far, and in some of the studied sites it has even statistically significantly decreased (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2018).

The same pattern is observed in populations formed by descendants of the primary introduction and located outside of Lviv (first group in Tables 3 and 4). In two of them, which had an unusually high proportion of banded shells (founder effect?), their frequency was higher among the collected empty shells rather than alive snails (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2022b: table 6). This could be interpreted as follows: 1) individuals with banded shells had a higher mortality rate; 2) this may cause a gradual decrease in the proportion of banded shells in populations, since collected empty shells belonged to adult snails of an earlier generation.

The unusually high proportion of unbanded shells in the Western Ukrainian populations of C. hortensis becomes particularly noticeable when compared with generalised data for its range as a whole (Schilder & Schilder 1957: table 13) or for different parts of this range separately (Cameron 2013: table 6). According to the summary table of the first authors, it can be concluded that unbanded shells are found in the natural range of C. hortensis, in general, no more often than banded ones (Sverlova 2002b). According to Cameron (2013: table 6), the average frequencies of unbanded shells in the Lviv (see above) and other Western Ukrainian populations of C. hortensis (Table 3) exceed those in any part of the natural range of this species. This is especially noticeable when compared with the average values given for a similar range of geographic latitudes (all the studied sites in Western Ukraine are located between 48 and 52°N): from 31 to 68% in the west, from 41 to 58% in the centre, and from 28 to 54% in the east.

We believe that the most likely reason for such high frequencies of unbanded shells in Western Ukraine is strong climatic selection outside the natural range (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021a). The advantages that Cepaea individuals with lighter shells may have in more continental climate have been discussed in detail previously (Gural-Sverlova & Gural 2021b: 375). Another possible explanation could be the common origin of most Western Ukrainian populations of C. hortensis in combination with random population genetic factors, primarily the founder effect. However, we can now state that the high proportion of unbanded shells (Table 3) in the majority of Western Ukrainian populations of this species (Table 4) is not associated with their general phenotypic composition (Table 3) and, accordingly, possible origin (primary introduction, mixed populations, secondary introductions).

Several recent publications have analysed the possible relationship between the level of phenotypic variability in introduced and/or urban populations of Cepaea and the time when they colonised certain areas (Cameron et al. 2009, 2014, Gheoca et al. 2019, Cameron & von Proschwitz 2020). It has been suggested that a high level of variability, assessed by the inbreeding coefficient Fst, is characteristic of recently populated areas, both within the natural range and outside it (Cameron et al. 2009). However, values of Fst can be influenced also by some other factors (Cameron & von Proschwitz 2020, Gural-Sverlova & Egorov 2021). Thus, low Fst values even in recently colonised areas outside the natural range may be related either to a common origin or to “a relatively uniform and rigorous selection regime” (Cameron & von Proschwitz 2020). Both the first and second are obviously true for populations formed by descendants of the primary introduction of C. hortensis to Western Ukraine. It is no coincidence that in Lviv the calculated Fst values for unbanded/banded and yellow shells are not only low, but are quite comparable with long established populations in England (Table 5), which is part of the natural range of C. hortensis. When including in the calculations a larger number of samples collected over much larger territories (several administrative regions in Western Ukraine), these values increase by 2–3 times even for primary introduction. However, even in the second and third groups of samples (Table 3), under the influence of secondary introductions of different origins, Fst for unbanded shells is significantly lower than in Sibiu or Sheffield (Table 5).

In the future, it would be desirable to conduct similar studies of C. hortensis in other parts of Ukraine, where colonisation by this species began recently due to secondary introductions and it is most likely occurring independently of the western part of the country, see above. Zhytomyr and Kyiv in Central Ukraine and Kharkiv in Eastern Ukraine now appear to be the most promising territories for this purpose. If the frequencies of unbanded shells there will be also high, and their spatial variability, characterised by Fst, is relatively low, this will be another argument in favour of strong climatic selection. Such research is especially interesting because the continentality of the climate in Ukraine increases from west to east. In the west of the country, more attention should be paid to the Transcarpathian region. Many reliable finds of C. hortensis have already been made there, but data on the phenotypic composition of its populations are very scarce. This may be interesting also in terms of possible climate selection, since C. hortensis is found both in the Transcarpathian Lowland with a warm and mild climate, and in mountainous areas.

Table 5

Inbreeding coefficient (Fst), calculated from the frequencies of two colouration traits, according to literature data and our research (three groups of samples from Western Ukraine are similar to Table 3)