INTRODUCTION

Since the seminal papers of Lamotte (1951) and Cain & Sheppard (1954) on the exuberant shell colour and banding polymorphism in the land snail Cepaea nemoralis (L.), there have been hundreds of papers dedicated to examining and explaining variation within and among populations of the snail. Detailed reviews are given by Cook (1998, 2008), and a shorter summary in Cameron (2016). Ożgo (2008) discusses unresolved problems in interpretation. The Evolution MegaLab (Silvertown et al. 2011) examined patterns across the whole range, and considered changes over time.

It is evident that no single explanation accounts for all the patterns of variation seen (Jones et al. 1977, Ożgo 2008). Variation with habitat, attributed both to visual selection for crypsis and to microclimate, is certainly widespread; variation with altitude and latitude are attributed to climate. Contraction and later expansion of local distributions influence morph frequencies through founder effects and genetic drift in small populations in isolation (Cameron & Dillon 1984). Despite some evidence for frequency-dependent selection (Clarke et al. 1978) and heterosis (Cook 2007), however, the maintenance of what appears to be a very stable and near-universal polymorphism remains in doubt.

In this context, the recent expansion of the species’ range eastwards, not only within Poland, and into Belarus, Russia, Ukraine and Romania (Ożgo 2005, 2012, Egorov 2018, Gheoca 2018, Balashov & Markova 2021, Gural-Sverlova et al. 2021, Gural-Sverlova & Kruglova 2022), but also in the Czech Republic to the south (Dvořák & Honĕk 2004, Peltanová et al. 2012), and in Sweden to the north (Cameron & Von Proschwitz 2019, 2020), has constituted an accidental experiment. It has also colonised cities within the natural range as industrial pollution has declined (Cameron et al. 2009). In some of these cases, a combination of deliberate introduction and accidental spread through horticultural trade can be documented, no doubt assisted by climate change. As Cook (2017) has suggested, the pattern of dispersal is leptokurtic, with some founding populations established a long way away from ancestral or any other populations.

In large cities, the evidence suggests multiple introductions from different sources, followed by very local, active dispersal (Cameron et al. 2014, Gural-Sverlova & Kruglova 2022). In villages and small towns, however, there are mostly merely first records, nearly always in anthropogenic habitats associated with human activity, often records of only one or a few populations. Variation among them over distances of 50 km or more appears greater than in districts within the natural range (Pokryszko et al. 2012) suggesting a multiplicity of sources. In this study, we report on more intensive surveys in two small towns, Skara in central Sweden and Kudowa Zdrój in south-west Poland, where we have evidence that the species’ arrival is recent, and no evidence of multiple colonisations or deliberate introduction. What is the local pattern of variation?

STUDY AREAS, MATERIAL AND METHODS

Both Skara (centred on 58º23'N, 13º26'E) and Kudowa (50º26'N, 16º14'E) are ancient settlements with much recent expansion. Both have a human population of c. 10,000. The first record of C. nemoralis in Skara was made in 2022; evidence from elsewhere in Sweden suggests that its arrival is no earlier than this century, and probably not more than 10 years ago. The land mollusc fauna of the Kłodzko region, including Kudowa, was surveyed in detail in the 1960’s (Wiktor 1964). C. nemoralis was not found. There are no records of the species from the adjacent part of the Czech Republic as at 1989 (Flasar 1989), and nearby sites were first detected between 1990 and 2010 (Peltanová et al. 2012).

Samples in Skara were all made by TvP between 2022 and 2025. Samples in Kudowa were made by RADC and the late Beata M. Pokryszko in 2007; they were entered in the Polish national database (cepaea5@uam.onmicrosoft.com) and later used in a national analysis (Ożgo et al. 2019), but are not separately published. Each sample in both towns comes from less than 30 m of typical anthropogenic habitats: roadside verges, hedges, garden or park boundaries, residential or commercial developments in progress. These vary in cover over very short distances, and no attempt has been made to classify them by shade or vegetation. The greatest distance between samples was 3.2 km in Skara, and 4.6 km in Kudowa.

Samples from Kudowa contain approximately ten times as many shells as those from Skara. We consider that this disparity reflects real differences in population density. Sites in Skara were searched very thoroughly, and some parts of the town, not evidently distinctive, lacked the snails. A site previously lacking C. nemoralis held a few specimens when searched in 2025. It appears to be spreading. Samples from Kudowa were made in winter, when the absence of snow cover revealed large numbers of fresh but empty shells, reflecting high densities in the previous active season. Because the samples in Kudowa were made opportunistically, the number made does not reflect distribution, which was widespread.

Shells were scored for colour and banding, following Cain & Sheppard (1954) and Jones et al. (1977). Among banding morphs, unbanded, mid-banded (00300), trifasciate (00345) and many-banded (with one or both upper bands present) were distinguished; more detailed scores, with details of fusions and the absence of particular bands are available for Skara samples from TvP. As unbanded is dominant over banded, the frequency of mid-banded is based on the number of banded shells. Trifasciate shells were very rare at Kudowa; at Skara, their frequency is based on banded shells other than mid-banded, which is dominant over other banding conditions.

Apart from considering the means and ranges of morph frequencies in relation to each other, and to other studies, we have attempted to assess the degree of polymorphism displayed, and the extent to which populations in each town differ from each other. The great difference in sample sizes between the two surveys complicates this. As elsewhere (Cameron et al. 2009) we have used a modified version of Wright’s (1978) Fst, the notional inbreeding coefficient, using morph- rather than allele-frequencies, adjusted by correcting for sample size, taking sampling variance to be p(1 − p) / n, where p is the mean frequency, and n the median sample size. The value obtained represents the proportion of the maximum differentiation possible for a given mean frequency.

RESULTS

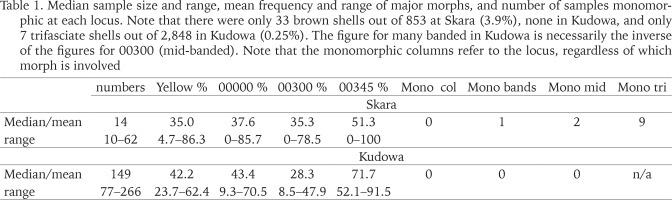

There are 46 samples from Skara, and 17 from Kudowa containing at least 10 shells. Their co-ordinates and composition are given in the Appendix. Table 1 shows median and range of sample size, the means and ranges of each morph frequency and the number of samples monomorphic at that locus. Table 2 shows the distribution of numbers of morphs among samples, and the value of the modified and corrected Fst for each colour and banding category.

Table 1

Median sample size and range, mean frequency and range of major morphs, and number of samples monomorphic at each locus. Note that there were only 33 brown shells out of 853 at Skara (3.9%), none in Kudowa, and only 7 trifasciate shells out of 2,848 in Kudowa (0.25%). The figure for many banded in Kudowa is necessarily the inverse of the figures for 00300 (mid-banded). Note that the monomorphic columns refer to the locus, regardless of which morph is involved

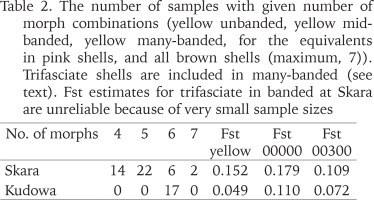

Table 2

The number of samples with given number of morph combinations (yellow unbanded, yellow midbanded, yellow many-banded, for the equivalents in pink shells, and all brown shells (maximum, 7)). Trifasciate shells are included in many-banded (see text). Fst estimates for trifasciate in banded at Skara are unreliable because of very small sample sizes

The mean frequencies of the major morphs (yellow, unbanded, mid-banded) differ slightly between the two towns, but are far from significant; variation within each is greater. The absence of brown shells, and the near absence of trifasciate shells in Kudowa are the only notable differences in composition. The occurrence of monomorphy, and the number of samples with less than the full complement of possible morphs in Skara can be attributed mainly to small sample size. The Fst values are notionally corrected for this effect.

The loci for shell colour and the presence or absence of bands are tightly linked. In Skara, there is a strong negative relationship between the frequencies of yellow and unbanded (r = −0.679, 42 df, p < 0.001) among samples, which merely reflects this linkage: yellow unbanded shells are missing in 28 sites; they make up only 12% of all yellow shells, but 54% of pink shells are unbanded. There is no such within-population disparity in Kudowa, where there is a marginal, non-significant tendency for unbanded to be more frequent in yellow shells rather than in pink.

We have not carried out a formal spatial analysis in either town. Inspection of the data in the appendix indicates that there is no significant spatial structure in morph-frequencies, with sites close to one another often having very different frequencies. Given the difference in sample sizes, those seen in Skara could be mere sampling error, but those in Kudowa are sometimes significant.

DISCUSSION

While absolute certainty is impossible, it appears that C. nemoralis is a recent arrival in both Skara and Kudowa. We have no evidence of deliberate introduction in either case, but the timing of their colonisation matches what we know of the species’ advance in Sweden (von Proschwitz 2022) and across the neighbouring Czech Republic for Kudowa (Peltanová et al. 2012). It seems likely that Kudowa had been occupied for longer before the survey than Skara, as the advance across Sweden has been monitored thoroughly.

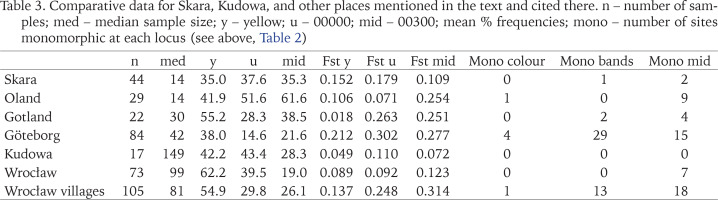

The most notable feature of populations in both towns is the maintenance of a high degree of polymorphism. Nevertheless, allowing for the effects of sample size, populations from Kudowa appear to retain rather more variation within populations and to differ less from each other (lower values of Fst). This suggests either or both of larger propagule size, or greater connectivity among populations. There is no evidence of spatial patterns in morph frequencies that might suggest multiple colonisations from different sources, as seen in studies of larger cities. Within Sweden, we can compare Skara with the islands of Oland and Gotland, as well as with the city of Göteborg (Table 3). While there are peculiarities in the patterns seen on the islands (Gotland has a known early introduction, and most samples come from a small urban area), populations there and in Skara are more uniform and polymorphic, especially for colour, than those from Göteborg, where the pattern resembles that seen in other cities recently colonised or recolonised, for example Minsk (Gural-Sverlova & Kruglova 2022), or Sheffield (Cameron et al. 2009).

Table 3

Comparative data for Skara, Kudowa, and other places mentioned in the text and cited there. n – number of samples; med – median sample size; y – yellow; u – 00000; mid – 00300; mean % frequencies; mono – number of sites monomorphic at each locus (see above, Table 2)

One feature of Skara populations is the very strong linkage disequilibrium at the colour and banding loci; the chromosome Y0 must be very rare. In the other Swedish studies this disequilibrium is weak in Göteborg, and effectively absent on the islands. It reinforces the evidence that a single initial introduction is the founder of present populations. Cook (2013) suggests that in the absence of strong selection, an initially strong disequilibrium will weaken over time.

In south-western Poland (Table 3) the boundary of the “natural” range is unclear, but outside of Wrocław itself, with a history of occupation by C. nemoralis and abundant and interconnected habitats since 1945 (Cameron et al. 2009), most populations, including those in Kudowa, are recently established. In a survey covering a much larger area than Kudowa (maximum distance between samples c. 70 km), Pokryszko et al. (2012), found that values of Fst were generally greater than in Kudowa or Wroclaw, and there were strong correlations between distance between samples and banding morph frequencies, such that the closer samples were, the more similar in morph-frequencies. In all three cases listed, linkage disequilibrium makes unbanded more frequent in yellow shells than in pink, significantly so in Pokryszko et al.’s (2012) study, a geographical trend noted by Wagner (1990).

While the difference in sample sizes between the studies in these two towns complicates comparisons, they certainly reflect real differences in density, and possibly the size of propagules. Taken together, these results suggest a pattern of small long-distance propagules passively dispersed, followed by local spread. Swedish populations do appear to be marginally less polymorphic; while there is some evidence for a reduction in the genetic diversity of newly-established populations and evidence of founder effects, they are modest; as Ożgo (2008) has forcefully pointed out, individual snails from a highly polymorphic population are likely to be heterozygous, and may carry stored sperm from more than one partner. As populations respond to new environments, we may expect to see changes related to habitat, which can occur rapidly (Ożgo 2011).