INTRODUCTION

The family Planorbidae represents the most diverse and species-rich group of limnic pulmonate gastropods, distributed across a wide range of freshwater habitats, including ponds, lakes, pools, and rivers (Pilsbry 1934, Burch 1982, Albrecht et al. 2007, Johnson et al. 2015). Globally, planorbids have been estimated to be approximately 350 species belonging to 40 genera (Baker 1945, Hubendick 1955). Helisoma scalare (Jay, 1839) is the most common, widespread and abundant planorbid species native to North America, and is now widespread in almost the entire world, probably due to release of aquarium specimens or introduction of fish (Alexandrowicz 2003, Seddon 2011, Johnson et al. 2015). This species is a medium-sized freshwater snail with planispiral shell, first found in Italy in 1986 in the Lake Albano (Latium, Italy) and reported as Planorbidae indet. (Mastrantuono 1990); then, it was found in Lake Nemi in 2001 (Mastrantuono & Sforza 2008). Despite this species being known for a long time, there are still uncertainties regarding its correct taxonomic placement. As a result, it has been referred to by various names over time: some authors identified it as Planorbella duryi (Wetherby, 1879), others as Helisoma scalare, and others as H. duryi (Wetherby, 1879). According to Glöer (2019) and Bodon et al. (2021) the populations of the lakes from Rome province could belong to H. scalare.

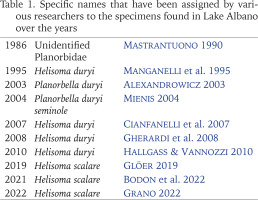

In fact, this species has long been the subject of a taxonomic controversy and has been called in various ways by researchers (Table 1). John Clarkson Jay described Paludina scalaris in 1839 from the “Everglades of Florida,” but recent research suggests the true type locality was Wakulla Springs, near Tallahassee. Similarly, Albert G. Wetherby described Planorbis (Helisoma) duryi in 1879 from the Everglades, though his population likely originated near Daytona, about 400 km east of Tallahassee. Neither locality lies within the modern Everglades Ecoregion.

Table 1

Specific names that have been assigned by various researchers to the specimens found in Lake Albano over the years

Overall, it has a planispiral, pseudodextrorotatory shell, with about 3–4 whorls, light or dark brown, translucent, and with deep sutures, a rough surface, a non-descending last turn, an oblique opening, and a sharp peristome (Brown & Lydeard 2010). Wetherby’s H. duryi had a shell wider than tall (planispiral), typical of Planorbidae. Pilsbry (1934) described four subspecies (normale, seminole, intercalare, eudiscus) which, along with duryi and preglabratum (Marshall, 1926), formed a continuous morphological gradient between H. duryi and H. scalare. Pilsbry (1934) noted these forms often occurred sympatrically and grouped them under the subgenus Seminolina, a view shared by Baker (1945).

Recent anatomical and morphological analyses found no clear distinction between H. duryi and H. scalare. Modern evolutionary theory, which disfavours sympatric subspecies, supports recognising only two typically allopatric forms: a scalariform form (taller than wide) and a planispiral form (wider than tall). Moreover, since Jay’s nomen scalaris/scalare is senior over Wetherby’s duryi by 40 years, the scalariform shell must be considered typical, with duryi the subspecific form.

Confusion also exists between H. scalare (especially its duryi form) and the widespread H. trivolvis. Juvenile H. trivolvis have fine spiral striations and a sharp apical keel, while H. scalare juveniles are smoother and glossier. The difficulty in reliably identifying species of the genus Helisoma has also been highlighted by Peter Glöer (personal communication, 2023), who pointed out inconsistencies between American and European specimens.

Pilsbry (1934), Baker (1945), and Hubendick (1955) placed scalare in Helisoma (subgenus Seminolina). Taylor (1966) elevated Planorbella to genus rank and reassigned scalare, a move followed by Burch (1982). However, as shell coiling axis is plastic in H. scalare/duryi, we favor the classification of Pilsbry, Baker, and Hubendick.

In this study, an anomalous and massive stranding of H. scalare shells was investigated, with a focus on the possible causes, the taxonomic status of this species, and the current ecological conditions of Lake Albano.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study area

Lake Albano (Fig. 1), also known as Lake Castel Gandolfo or Lake Castello, is located in the Latium region of central Italy, at an elevation of 293 meters above sea level, approximately 24 km southeast of central Rome (Grano 2022). The lake occupies a deep volcanic crater within the Colli Albani range, which preserves the prominent geomorphological features of the so-called Vulcano Laziale. This volcano represents the southernmost and final phase of a chain of Quaternary volcanic complexes (Volsinii, Vico, and Sabatino) aligned along the Tyrrhenian margin of central Italy.

Following the cessation of volcanic activity around 40,000 years ago, several craters within this volcanic district became filled with water, giving rise to a series of crater lakes. Lake Albano is approximately oval in shape, measuring ~3.5 km in length and ~2 km in width, with a surface area of 6.02 km² and a maximum depth of 170 meters. Despite its modest surface area, it is the deepest volcanic lake on the Italian Peninsula and is characterized by some of the steepest lake margins.

The crater is enclosed to the west, south, and east by high (150–250 m) and extremely steep inward-facing slopes composed primarily of pyroclastic deposits and, in part, basaltic rock outcrops. In contrast, the northern rim of the crater features more gradual and lower slopes (Caputo et al. 1974, Alexandrowicz 2003).

The sand along the shoreline is grey to black in colour, primarily composed of fine pyroclastic material mixed with basaltic grains. The crater hosting Lake Albano formed during the terminal phase of volcanic activity, as an eccentric eruptive center within the western sector of the Vulcano Laziale. This phase is dated to the Late Quaternary (27,000–20,000 years BP) and corresponds to the last glacial period, known as the Würm or Vistulian glaciation (Cosentino et al. 1993, Casto & Zarlenga 1996).

Lake Albano is primarily fed by sublacustrine springs and is equipped with an artificial emissary constructed by the Romans in 398–397 BC near the town of Castel Gandolfo (Medici 2007).

Bathymetric studies have revealed three distinct sublacustrine platforms. The first is located 10–12 meters below the water surface and is adjacent to an 80-meter escarpment. A second, ring-shaped platform occupies a more central position, bounded by a slope ranging from 35 to 50 meters in height. The third and deepest platform lies at the bottom of the lake, at an elevation of 126–133 meters a.s.l., and is overlain by approximately 14 meters of sediment accumulation (Anzidei et al. 2006, Bozzano et al. 2009).

Sampling

A massive stranding of Helisoma scalare was recorded in January 2025 along the northwestern shoreline of Lake Albano (Fig. 1). A visual survey was carried out to delineate the spatial extent of the stranding, followed by specimen collection (Figs 2–6). Samples were randomly gathered along the shoreline, focusing on areas where the presence of the species was most conspicuous. A total of 500 individuals were randomly collected in situ and 150 of them were measured. For morphometric analysis, shell height as measured from the apex to the base of the aperture, and shell width at the widest point, from the lateral margin of the body whorl to the outer edge of the aperture, with the aperture oriented toward the observer.

RESULTS

The shoreline most affected by the stranding spanned approximately 3,000 m. Shell accumulations formed continuous belts extending 8–10 m in length and 80–100 cm in width, with a maximum thickness of about 5 cm. The specimens displayed the typical scalariform shape, with thick, flat to slightly concave straw-colored shells, weakly undulated by indistinct transverse ridges and a regular spire. Morphometric analysis of the sampled individuals (n = 150) yielded a mean width of 9.90 ± 3.24 SD and a mean height of 8.94 ± 2.52 SD (Figs 7–15). It should be specified that all sampled specimens were found devoid of any soft tissue remains and often with partially eroded shells; no living individuals were observed.

Figs 7–15

Collage with photos of several Helisoma scalare specimens of different sizes. A large specimen is at the top (7–9), a medium-sized one in the center (10–12), and a smaller at the bottom (13–15). Scale bars 5 mm

In addition to H. scalare, a few individuals of Radix auricularia (Linnaeus, 1758) and Bithynia spp. were recorded; additionally, isolated calcareous accumulations were observed, comprising both Bithynia opercula and carbonate structures that remain unidentified. The accumulation of H. scalare shells was markedly higher in sandy sediment zones, whereas coarse sediments, pebbles, and boulders hosted only limited deposits, suggesting that hydrodynamic forces (currents and wave action) influenced mollusc distribution and deposition.

DISCUSSION

Baker (1945) suggested that planorbids of the subgenus Seminolina, including H. scalare and H. duryi with their subspecies, were restricted to peninsular Florida. However, H. scalare is widespread throughout southern Florida and extends northward through coastal Georgia and South Carolina to at least the Myrtle Beach area, inhabiting both disturbed habitats and more pristine environments such as the Black River, often in sympatry with H. trivolvis. Outside North America, populations of H. scalare have been reported from Asia, Africa, Europe, and South America (Brown 1967, Pointier et al. 2005, Fernandez et al. 2010), sometimes intentionally introduced for schistosomiasis control. Laboratory studies have shown strong negative interactions with Biomphalaria and Bulinus (Frandsen & Madsen 1979, Madsen 1979, 1982, 1984, 1987), potentially mediated by egg predation (Meyer-Lassen & Madsen 1989) or direct antagonism (Madsen 1986). Despite its invasive capacity, populations have occasionally disappeared after localised or sporadic establishment (Giusti et al. 1995). Overall, the species is strongly associated with anthropogenic environments (Mienis & Rittner 2012), and its spread is mainly linked to the trade of tropical plants (Pons et al. 2003) and aquarium releases (Appleton 1977, Cianfanelli et al. 2007, Mienis & Rittner 2012). Indeed, it is a common ornamental species in aquaria, marketed as the Ramshorn snail in various colour morphs (brown, leopard, blue, red/orange, pink, green, purple).

Although little is known about the biology of wild populations of this species in their natural range, exotic populations and aquarium cultures have been well studied. Some of the best population dynamics data available for any freshwater gastropod have been published for laboratory stocks of H. scalare by de Kock & Joubert (1991).

Lake Albano has very marked peculiarities able to determine drastic biocenotic variations and this can lead to the disappearance and sudden reappearance of these aquatic molluscs (Grano 2022). Furthermore, despite the fact that species found within the stranded accumulations do not reflect the true malacological diversity of the lake, previous studies have reported low species richness along the sandy littoral zones adjacent to the shore (Mastrantuono 1995). This lake, being devoid of natural outflow streams, is subject to important variations in level, especially in response to atmospheric precipitation. In the artificial outflow stream, since 1992, the water in excess of the lake no longer flows (Medici 2007). The lake shows clear signs of eutrophication, such as persistent algal formations (Medici & Rinaldi 2004, Medici 2005, 2007), and is further affected by organic water pollution, mainly due to high anthropic pressure (De Liberato et al. 2019). The distributions of Euglesa spp. in the lake and also of other indicator taxa belonging mainly to tubificids and chironomids suggest the existence in the lake of three biologically different zones, the first of which (20–35 m) still considered to be in acceptable conditions. In the range between 50 and 95 m, an increasing degradation of water quality has been highlighted and a complete absence of fauna below 120 m depth has been observed. Thus, depth distribution of benthic fauna in Lake Albano clearly reflects the environmental stress caused by the vertical oxygen decline (Bazzanti et al. 1993). The Albano Lake area is a site of several hazardous processes, including slope instability inside the crater, lowering of water level, hydrothermal circulation, seismicity, uplifts, and gas emissions of H2S and CO2, with stratification of gas concentrations reaching 200 mg/l of CO2 at the bottom. Additionally, tsunami waves as secondary effects of subaqueous landslides have been inferred (Barberi et al. 1989, Carapezza & Tarchini 2007, Chiodini et al. 2012).

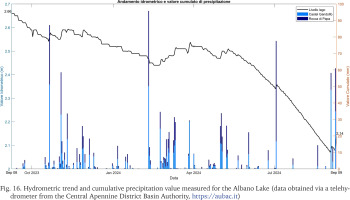

The collection of Helisoma scalare shells revealed the presence of specimens belonging to multiple size classes without showing clear dominance. All sampled specimens exhibit a completely white shell, sometimes more fragile and eroded on the surface. Internally, no soft tissue remnants of the organism are present, suggesting that death did not occur immediately before the stranding event but rather at an earlier time. The specimens show evident signs of abrasion, presumably due to the friction of the shells against the substrate. It is important to note that, at the time of the stranding, despite field surveys being conducted both in areas of the lake covered by macrophytes and in those characterised by unconsolidated sediment, no living specimens were observed. As a consequence, this evidence indicates that the occurrence of this massive stranding event in living specimens is improbable. So, it cannot be ruled out that these specimens originate from lakebed thanatocoenoses that resurfaced and were reintroduced into circulation by meteorological events and superficial lacustrine currents, facilitated by water level reduction. This hypothesis is further supported by localised calcareous accumulations containing Bithynia spp. opercula and unidentified carbonate elements, likely derived from the same sediments resuspended by the lowering of water levels and redistributed by waves and tides, resulting in heterogeneous deposition. In fact, it is estimated that the waters of Lake Albano have lowered by approximately 7 meters over the past 40 years, with a reduction peaking at around 50 cm between 2023 and 2024 (Fig. 16; data obtained via a telehydrometer from the Central Apennine District Basin Authority, https://aubac.it). This leaves multiple hypotheses open regarding the explanation of such accumulations, but further investigations are needed to more accurately determine the cause of an event of this magnitude.

Fig. 16

Hydrometric trend and cumulative precipitation value measured for the Albano Lake (data obtained via a telehydrometer from the Central Apennine District Basin Authority, https://aubac.it)